Imagine the reliable fuel pump at your local duka suddenly switched off one Friday afternoon – that’s what happened when KOKO Networks abruptly halted operations in Kenya. This Kenyan startup had built a network of ~3,000 automated ethanol “fuel ATMs” to sell bioethanol cooking fuel to low-income households. It sold the fuel for roughly KES 100 per liter (about half the price of kerosene) and subsidized stoves, relying on carbon credit sales to cover the losses. When Nairobi wouldn’t sign off on those credits, KOKO’s business collapsed overnight. Reports say over 700 employees lost their jobs and roughly 1.5 million urban households suddenly had no cheap clean cooking option.

KOKO’s model worked only with carbon finance. In simple terms: they let poor families cook with cleaner fuel at a discount, then sold the avoided CO₂ and smoke emissions to global buyers (e.g. airlines under ICAO’s CORSIA scheme) as verified carbon credits. These credits were Gold Standard-certified – roughly 1 ton CO₂ saved per credit – fetching $20 or more each in compliance markets (far above the low voluntary market prices). KOKO even took out a $180 million political-risk insurance from the World Bank’s MIGA to cover this gamble. But when Kenya’s regulators refused to issue the needed paperwork, the revenue stream dried up. In a word, the math “simply didn’t work anymore” without those carbon dollars.

Article 6 and Letters of Authorization: Carbon Credits vs. Kenya’s Climate Targets

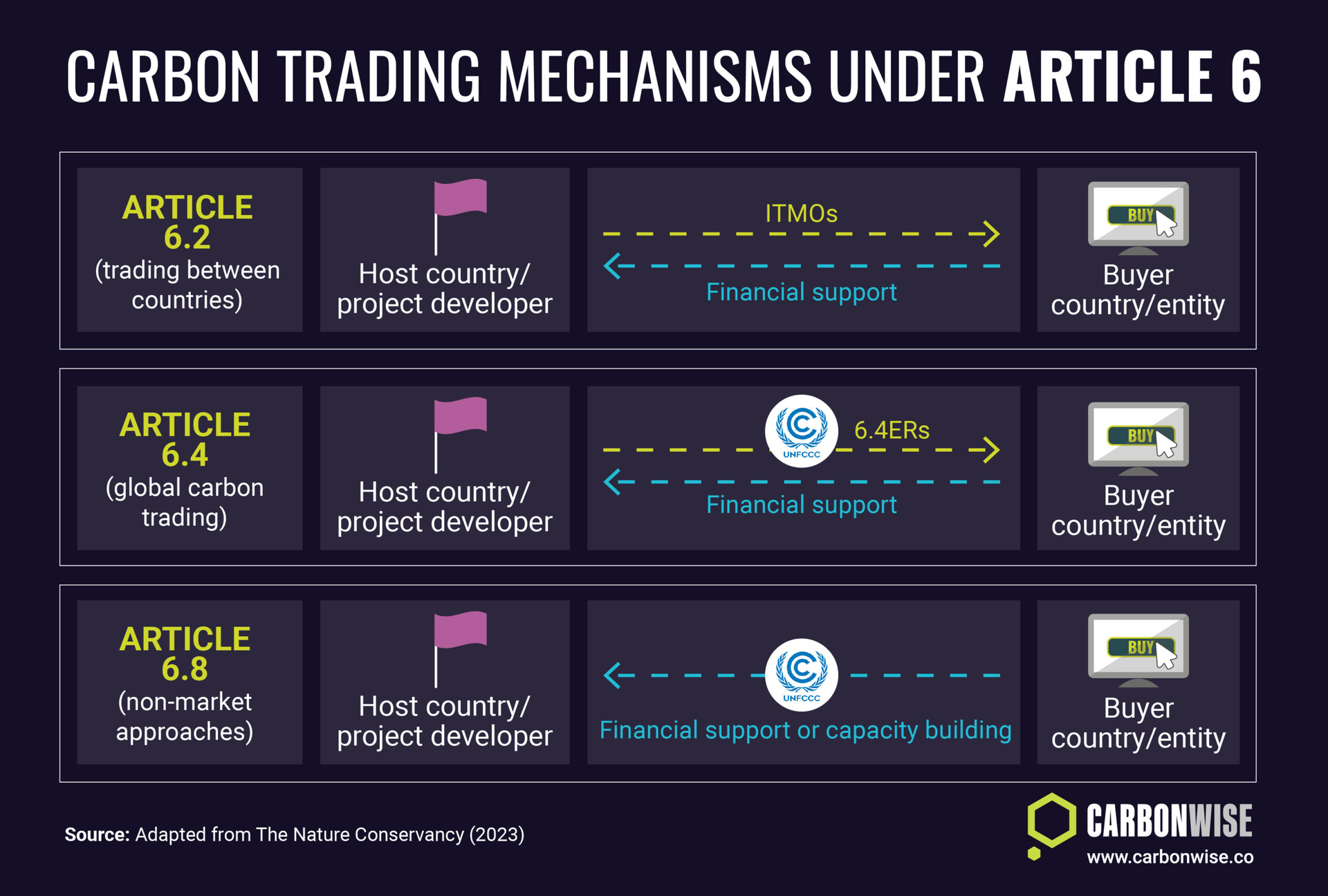

At the heart of the crisis is Article 6 of the Paris Agreement – the rulebook for international carbon trading. Under Article 6, any credits sold abroad require a formal Letter of Authorization (LOA) from the host country, plus a “corresponding adjustment” in its climate accounts. In practice that means Kenya must not count a sold emission reduction in its own tally. For KOKO, this was fatal. By one account, the government simply sat on the LOA: officials worried that if they let KOKO export too many “savings,” there wouldn’t be enough left to meet Kenya’s own Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC). An Argus report notes the hold-up was exactly this: “the government’s uncertainty about its capacity to grant corresponding adjustments while retaining enough emissions reductions to meet its Paris Agreement targets caused the delays”.

In other words, Kenya didn’t want to let KOKO take a large portion of its carbon budget away. Without the LOA, KOKO’s credits were useless outside Kenya. As KOKO’s board warned, lacking government sign-off meant bankruptcy was “immediate”. It’s a classic tension: the country must protect its climate goals, but the company needed to monetize the very reductions Kenya had pledged to cut. In the end, after even signing a 2024 investment framework with KOKO, Nairobi quietly declined to issue the authorizations.

Kenya is trying to address this clash. In mid-2025 it unveiled draft carbon market regulations, including a digital National Carbon Registry to track every project. These rules explicitly tie what can be sold abroad to Kenya’s NDC limits: only emissions “beyond existing commitments” may be turned into credits. The idea is to avoid double-counting and ensure every credit represents real extras. The registry is even designed to include small farmers, foresters and communities, not just big developers. In short, Kenya is starting to lay down ground rules for accountability and transparency – but the system is brand-new, and regulatory “teething problems” like KOKO’s suggest there’s still a way to go.

Investors, Insurers and “Chilling Signals”

The KOKO saga has rattled both local and international stakeholders. Domestically, President Ruto’s own adviser David Ndii publicly questioned the business. He bluntly pointed to “veracity of cookstove carbon credit and lack of transparency in the firm’s business model” as culprits, blaming not just KOKO but an “investor-unfriendly NDC regime” and murky carbon regulations. In other words, top officials are saying: maybe the problem wasn’t just our bureaucracy but also whether the carbon cuts were real and fairly accounted.

Abroad, climate financiers took note. KOKO had raised about $300 million (half of it on physical infrastructure) from funds including Microsoft’s Climate Innovation Fund, Mirova and Rand Merchant Bank. Those investors are likely preparing for legal action: indeed, KOKO intends to claim under the World Bank’s Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency (MIGA) cover, since Kenya agreed in advance to pay out if it ever blocked their carbon trades. On the markets, CORSIA futures briefly tumbled when news broke that Kenya wouldn’t approve the credits. And analysts warn that KOKO’s collapse is a “chilling signal” to the global climate finance sector – a reminder that even “high-integrity” projects can die on the vine if policy keeps shifting.

Who Gets Paid? Transparency, Equity and Land Rights

Beyond bureaucratic snags, many Kenyans worry about fairness and justice in carbon deals. On one hand, community projects like mangrove forestry show the upside: villages in Gazi Bay and Vanga (coastal Kenya) have sold mangrove “blue carbon” credits, earning nearly $200,000 for local development (new wells, schools and hospitals) while preserving vital ecosystems. That’s a model of carbon finance working for ordinary people.

On the other hand, controversial projects in northern and southern Kenya have sparked protests and court fights. In the north, the huge Northern Rangelands Trust (NRT) carbon project – which set up wildlife conservancies and grazing restrictions – was twice suspended by Verra (the certifier) after courts and tribal elders accused it of creating conservancies on Indigenous land without proper consent. In Kajiado County, Maasai villagers famously stood up at a meeting and shouted “Hapana Carbon!” (“No Carbon!”), blocking a 68,000-hectare land lease for a soil-carbon project. These incidents have fed a broader narrative of “carbon colonialism,” where outsiders make deals on ancestral lands without fair benefit-sharing or even genuine community approval.

A section of Oldonyonyokie Group Ranch members in Kajiado County hold a meeting to oppose a carbon credits scheme on April 30, 2025; SOURCE: Nation Media

Rights groups have documented harsh outcomes in such schemes. Survival International’s “Blood Carbon” campaign details how one rangelands project armed park rangers to enforce new grazing rules, reportedly leading to “dozens of horrendous human rights abuses, including murder” against pastoralists who were cut off from their livestock. (These abuses may sound extreme, but they highlight the real fears on the ground.) The upshot is a call for transparency and equity: Kenyans rightly ask who audits these projects, how the credits are calculated, and whether local families see any real income instead of just losing land or grazing.

Even KOKO itself came under scrutiny: a 2024 UC Berkeley study warned that many cookstove carbon projects had “saved only a fraction of the carbon emissions claimed”. This bolstered concerns that the credits KOKO counted on might not have been as solid as advertised. If credits are overestimated, the climate benefit is fake, and yet communities (and Kenya’s carbon budget) still pay the price.

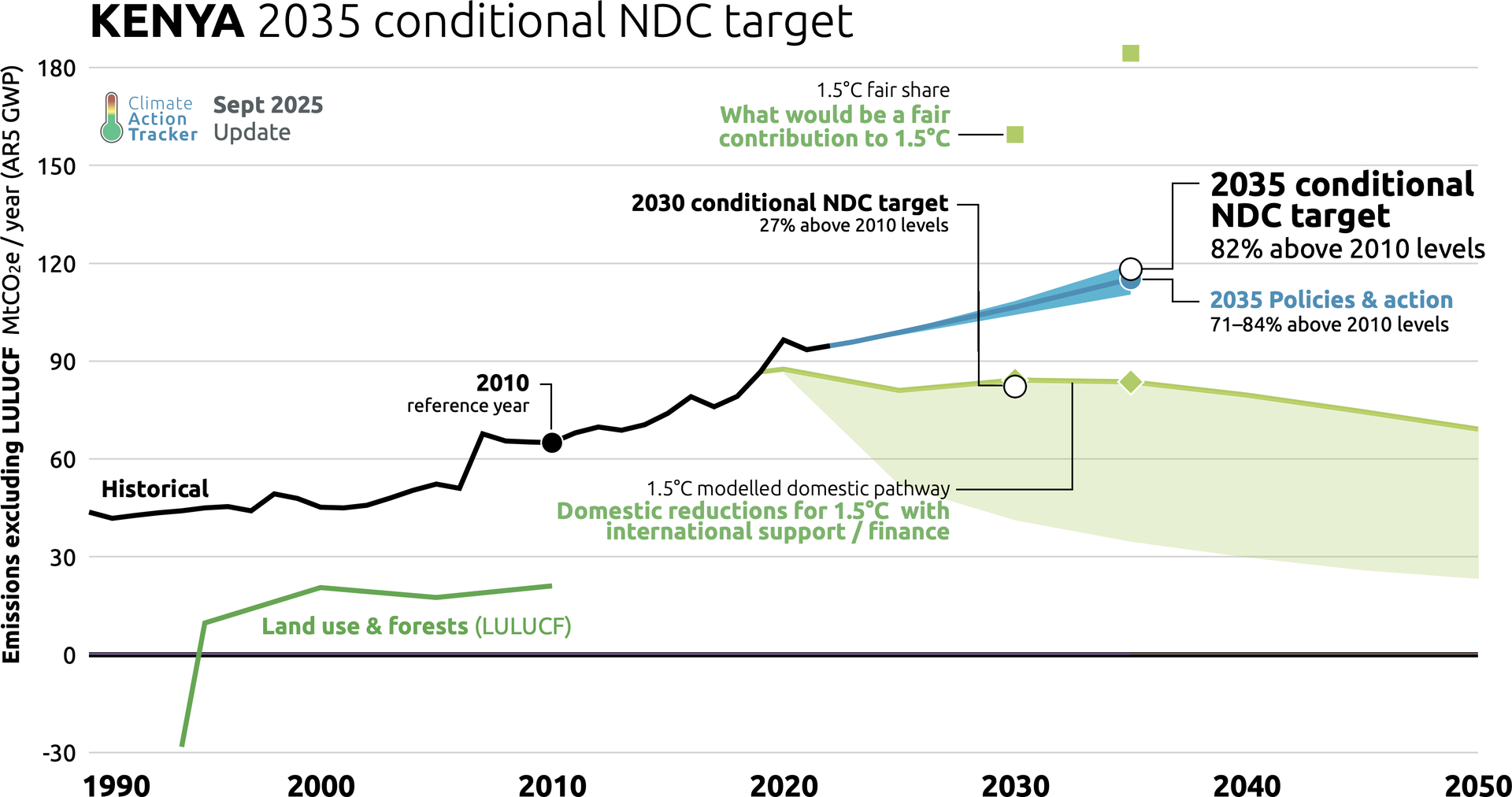

Kenya’s Climate Targets and Carbon Markets

All this sits within Kenya’s bigger climate promises. In April 2025 Kenya submitted a new NDC pledging a 35% emissions reduction by 2035 relative to a “business-as-usual” scenario – roughly 75 million tonnes of CO₂ avoided. However, only 20% of that 75 Mt is to be achieved “domestically”; the remaining 80% hinges on international support like climate finance, technology transfers and carbon markets. In plain terms, Kenya is counting on foreigners (and global markets) to help it meet its cuts.

Source: Climate Action Tracker

Climate analysts point out the risk here. The Climate Action Tracker notes that targeting cuts from a rising BAU baseline (and selling off the rest) can make the pledge look strong on paper even if actual emissions keep climbing. It warns that if Kenya “considers selling emissions reductions under Article 6, [it] risks undermining ambition if the credits do not represent real, additional and permanent reductions”. In short: if too many credits are hyped, the net effect could be a weaker climate outcome. This underscores the balancing act: Kenya wants to both be ambitious and reap carbon revenues, but one cannot cannibalize the other.

When Carbon Finance Delivers: Opportunities Ahead

So far we’ve heard why people are worried. But there are opportunities if Kenya plays its cards right. The key is high integrity and local buy-in. For example, the coastal mangrove projects above show that when communities co-design a scheme, everyone wins. Carbon finance can fund mangrove replanting (protecting communities from storms and erosion) and also pay for schools or boreholes, creating a virtuous cycle. Kenya’s draft rules even aim to extend that model inland: by requiring every project to be in a public registry, small farmers and pastoralists could potentially earn for climate-smart practices on their land.

Ambassador Ali Mohamed delivering a keynote at the 'Harnessing Mobile Money & Remote Monitoring for Kenya's Carbon Markets Ecosystem' event

Kenya is also stepping up on the global stage: in 2025 our own Special Climate Envoy Amb. Ali Mohamed co-hosted the Coalition to Grow Carbon Markets with Singapore and the UK. This initiative is pushing for clear rules and demand for good credits. The goal is to unlock big climate dollars (an ambitious USD 250 billion by 2050) to flow into vulnerable countries. If Kenya’s projects meet strict standards (and really benefit people), we could see billions in foreign investment for Kenyan forests, farms and clean energy.

In short, carbon markets aren’t inherently bad. They can finance tree-planting, wetlands protection or cleaner cookstoves that wouldn’t happen otherwise. The devil is in the details: ensuring emissions accounting is fair, double-counting is prevented, and communities share in the profits.

Building a Kenyan Carbon Conversation

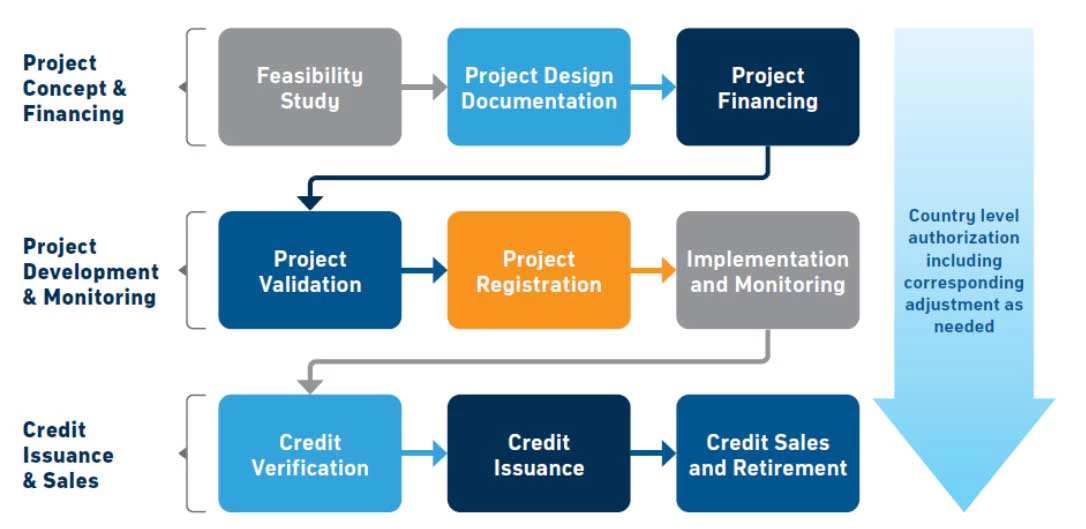

Life cycle of a carbon project; World Bank

The KOKO Networks collapse was a dramatic wake-up call. It shows that climate solutions must fit Kenya’s reality. We need to ask ourselves: who sets the rules? Whose voices get heard? Which projects really help the climate and our people? The case for conversation is clear. In community halls and Parliament alike, Kenyans – especially the youth, local leaders and activists – should shape how carbon markets grow here.

Consider this: a carbon offset system that balances climate goals with justice and local benefit might invest in solar mini-grids for rural dukas, or pay Maasai herders to restore degraded rangelands. It might finance village-run water projects via mangrove protection – not arm guards blocking grazing rights. It will be transparent about numbers so that when a credit is sold, everyone trusts the cut is real.

No single model is perfect yet. But one thing is certain: Kenya has the creativity, the talent and the urgency to craft its own path. As we reflect on KOKO’s story, let’s talk openly about what a fair carbon market looks like for us. Will it be one that protects our forests and funds our schools, or one that simply lets outsiders tick a box while we clear more wood for fire? The answer matters – not just for our climate commitments, but for how communities across Kenya will live and thrive.

The future carbon market will only be as strong as the trust it earns. Let’s start building that trust together, so everyone wins.